The Illustrious (& Outrageous) History of Vin Mariani

14th March 2017

Share This Post

Created in 1863 by Angelo Mariani, a French chemist who became intrigued with coca and its economic potential after reading Paolo Mantegazza’s paper on coca’s effects. The ethanol in the wine acted as a solvent and extracted the cocaine from the coca leaves, altering the drink’s effect. It originally contained 6 mg of cocaine per fluid ounce of wine, but Vin Mariani that was to be exported contained 7.2 mg per ounce, in order to compete with the higher cocaine content of similar drinks in the United States. Advertisements for Vin Mariani claimed that it would restore health, strength, energy, and vitality.

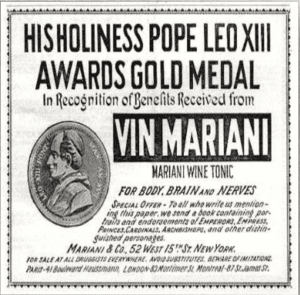

Vin Mariani was very popular in its day, even among royalty such as Queen Victoria. Pope Leo XIII and later Pope Saint Pius X were both Vin Mariani drinkers. Pope Leo awarded a Vatican gold medal to the wine, and also appeared on a poster endorsing it.

Thomas Edison also endorsed the wine, claiming it helped him stay awake longer. Ulysses S. Grant was also a fan of the wine, which he began drinking while writing his memoirs towards the end of his life.

The study inspired Mariani to combine ground up coca leaves with red Bordeaux wine, at the rate of 6 milligrams of coca per ounce of wine, and thus Vin Mariani was born. A proper ‘dose’ was two to three glassfuls per day, taken before or after meals (halved for children!). The product was marketed as a digestif, an aperitif, and a general cure-all. The delicious concoction promised to heal whatever ailed you and provide the energy boost needed by actresses, inventors and workingmen alike.

Vin Mariani was a massive hit. Mariani’s wine and coca tonic took his home city of Paris by storm, and then, the rest of Europe and the U.S. Seizing on the opportunity, Mariani opened offices in London, New York and Montreal. To support demand for his product in the U.S. he opened a second laboratory in New York. Vin Mariani had many competitors and imitators, but a shrewd, celebrity-driven marketing campaign earned him millions of dollars worth of sales. While Mariani’s ads claimed that thousands of doctors endorsed the product, it was the celebrity endorsers who really pushed the elixir. The ads he ran in newspapers and magazines featured countless politicians, actors, writers and religious leaders, all extolling the many virtues of Vin Mariani. Devotees of the drink included Alexander Dumas, Emile Zola, Presidents William McKinley and Ulysses S. Grant, and countless monarchs including Queen Victoria of England. In addition, actress Sarah Bernhardt and Pope Leo XIII (who gave him a Gold Medal!) were among the many who actually appeared in advertisements.

Another ad revealed that the Pope was a true believer in the product:

“His Holiness THE POPE writes that he has fully appreciated the beneficiary effects of this Tonic Wine and has forwarded to Mr. Mariani as a token of his gratitude a gold medal bearing his august effigy.”

Mariani was the first to collect celebrity endorsements and use them to sell his own product. Mariani’s early advertising campaigns were aimed mainly at doctors. He would send the doctors free wine samples, asking that in return they send him an endorsement for his product. By 1902, Mariani had amassed letters of praise from more than 8000 physicians and other happy clients from around the world.

Mariani also wrote and printed scientific brochures and monographs , and these too were distributed free of charge to physicians. Not surprisingly, the brochures always contained endorsements, if not from media stars and artists, then from physicians claiming impressive cures. Leaving nothing to chance, Mariani also advertised in the Paris newspapers. Prominent graphic artists, such as Cheret and Robida, were commissioned to produce graphics for those newspaper advertisements. The same artists were paid to draw posters that were displayed around Paris. There was also a line of medallions and plaques, each with a different Vin Mariani endorsement .

A total of 1086 celebrity portraits was published. The list of celebrities included three popes, sixteen kings and queens, and six presidents of the French Republic. There were also painters, sculptors, composers, actors, politicians, generals, bishops, physicians, and respected scientists. Most of the profiled celebrities were French, but Americans were not totally ignored. Later editions to the series included both the investor Thomas Edison and the actress Sarah Bernhardt. Different celebrities made different kinds of contributions. H.G. Wells drew two small cartoons of himself. In the first, he was slouched and depressed. In the second, a happy-looking Wells is shown drinking Vin Mariani. President William McKinley’s secretary, John Addison Porter, wrote to Mariani and thanked him for the case of wine he sent to the White House. Porter assured Mariani that the wine would be used whenever the occasion presented itself. A complete set of these endorsement albums can be still be seen at the British Museum.

The celebrity folios were expensive and were designed to reach an influential, if limited, audience. To increase product recognition, Mariani reprinted extracts taken from the folios. He republished biographies of individual celebrities and issued them as bulletins. The bulletins were then inserted in local papers around Paris. These bulletins, or supplements, were similar to the promotions used by supermarkets and department stores today. The supplements were folded into the centers of leading Parisian newspapers under the title, Contemporary Figures. Each issue was 16 pages long, and measured 32 cm x 23 cm.

This advertisement, with a picture of the Pope, appeared in a London newspaper in 1899. A complete collection can be seen at the British Museum. From the author’s private collection.

The magnitude of Mariani’s promotional campaigns is hard to grasp. He printed 800,000 copies of Contemporary Figures at a time, and had them inserted into Le Journal, Le Monde, L’Eclair, Le Figaro, and half a dozen other major newspapers. Over the 20 years of publication, more than 64 million issues of Mariani’s Contemporary Figures were distributed. Mariani squeezed additional mileage out of the supplements by taking individual photographs from the albums and reprinting them as postcards. Four different series, each comprised of 30 cards, were printed and sold for 10 cents a card.

Not only did Mariani like to be surrounded by the rich and famous, he also emulated their lifestyle. His dedication to coca was evident everywhere. By the turn of the century, he constructed large greenhouses, filled with thousands of coca plants, on his estate. He also constructed a laboratory, a production plant, and a large art nouveau salon, built of elaborate glass and wrought iron. Images of coca plants were woven into the rugs and curtains, and even the floor tiles and ceiling moldings were decorated with a coca leaf motif. He commissioned Eugene Courbin to paint his office ceiling with an allegory of “The Goddess Bringing the Coca Branch to Europe.” Coca leaves were carved into the chairs and sofas, and rooms were decorated with artificial coca plants in ceramic pots.

Like the makers of Coca-Cola, Mariani never disclosed the formula for his famous wine, saying only that he used a “fine” Bordeaux and only “the finest coca leaves.” Actually, the formula for coca wine was no secret. The French government had set guidelines for its manufacture, and any pharmacist could produce it. The formula was simplicity itself. Sixty grams of ground coca leaves were soaked for 10 hours in 1 litre (2.1 pints) of red or white wine, containing 10% to 15% alcohol.